I recently made a web app that helps you play Wordle, everyone’s favorite word game. In case you haven’t heard of it, Wordle is a game where you try and guess a 5 letter word in 6 tries (just Google it!)

Click here to go to my website and try it out.

I thought it might be worth sharing the engineering of how I designed, wrote and published this app. Plenty of people have written much better wordle solvers than mine, using cooler techniques like information theory, unlike my very naive heuristic. I also really like Norvig’s simple 4 word solution, designed to be memorizable and usable without the aid of a machine.

So why is mine special? Well, I designed Wordle Helper with these goals:

- Runs everything locally, no need for a backend server.

- Response time under 10ms, the threshold for instantanous feedback

- Suggest words that a human would guess, not necessarily one that is mathematically optimal

- Fast build times as a developer

I’m going to focus this article on how I managed to achieve those goals.

1. Starting out

I got the Wordle word list from the website itself. Wordle has an internal word list of 2047 words which it just rotates through daily - that’s what the 248 in Wordle 248 represents.

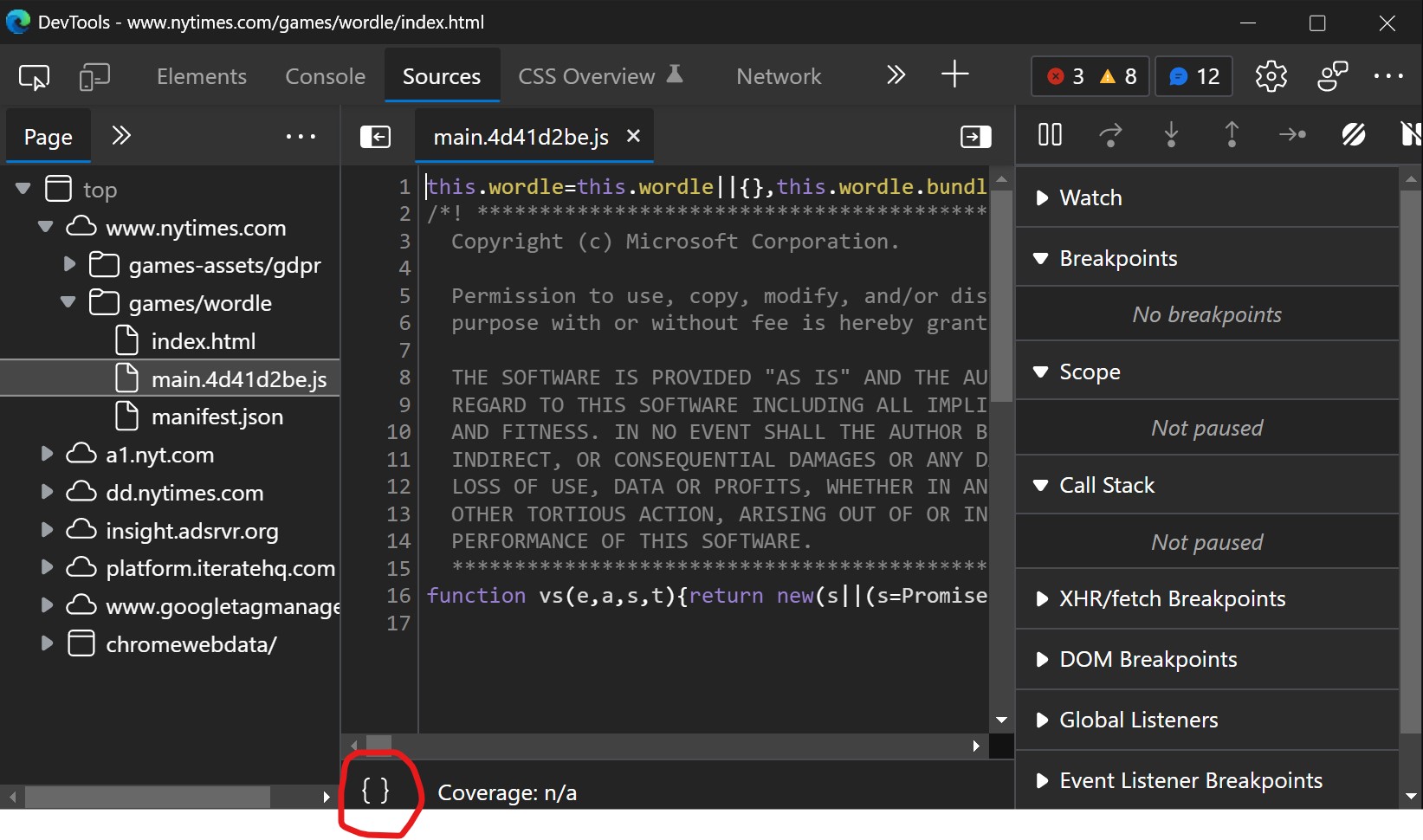

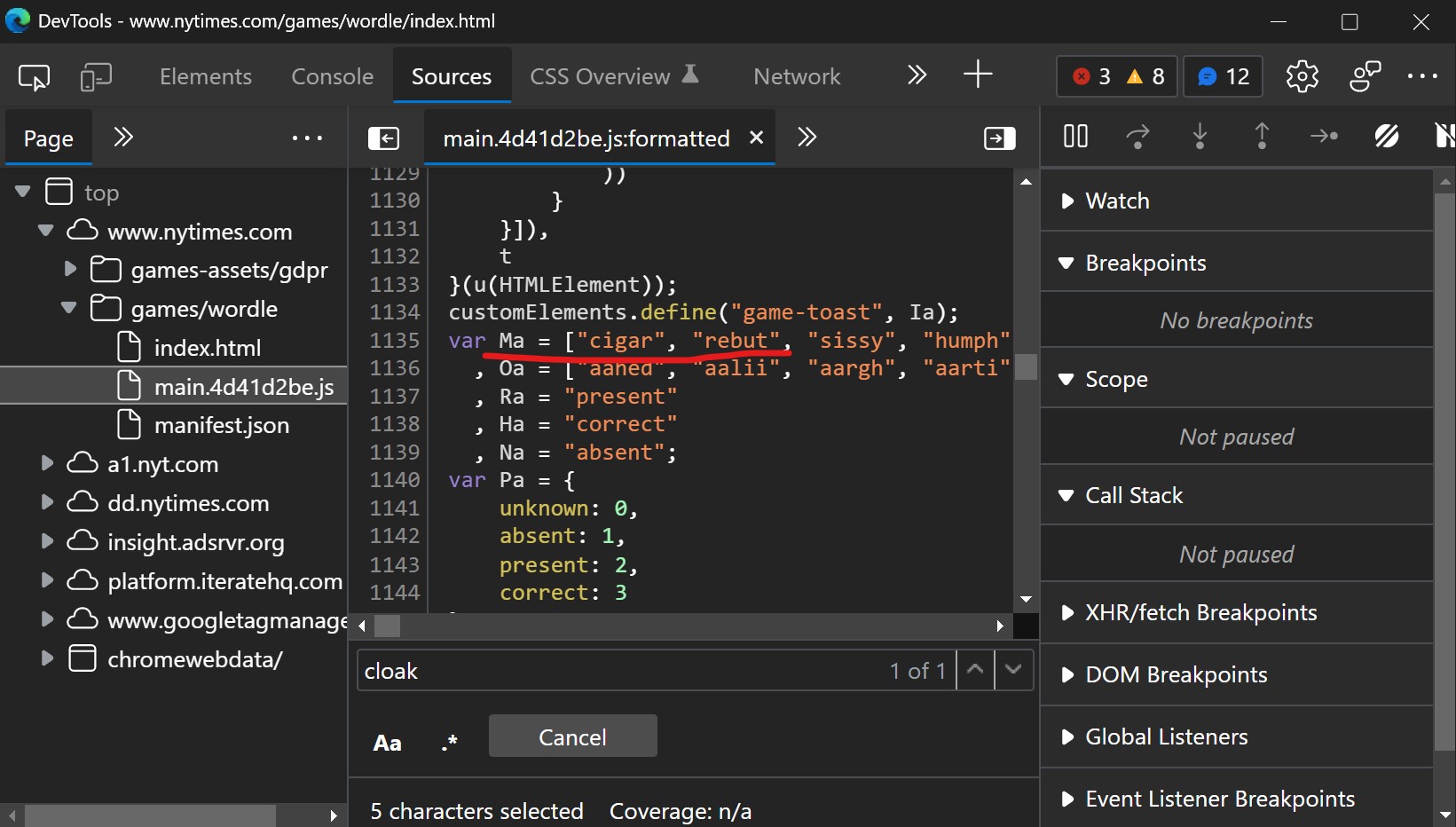

You can easily find the word list by going on the Wordle web site, going to the main.js file in the Sources tab, then click on pretty print. Once the js is pretty printed, just search for a Wordle word like “cloak” or “cigar”, and the word list pops up pretty quickly. In the second picture below, it’s assigned to the variable Ma.

Once I got this copied into a text file, I immediately sorted it to avoid spoilers. The answers appear one after the other, so if you see the word in position 249, that’s the answer for day 249.

I started out by writing the HTML and Javascript inline directly, copying my other website x86 flags. It looked something like this:

1<!doctype html> <html lang="en">

2<head>

3<meta charset="utf-8">

4<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1, shrink-to-fit=no">

5<meta name="description" content="Your description here">

6<meta name="author" content="Thomas Tay Ang Chun">

7<script type="text/javascript">

8 'use strict';

9 function update() {

10 // more here ...

11 }

12</script>

13<body>

14 <h1>Enter your guesses here</h1>

15 <input id="input1" oninput="update()"></input>

16 <!-- more here... -->

17</body>

Lesson #1: If you’re overwhelmed by the JS build ecosystem, you can just start by writing inline JS in a HTML file. Don’t let people shame you for it. I did it for X86 flags and it worked out fine.

However after about a day of writing code, the JS part of my file was growing larger and larger, so it was time to set up a build system.

2. My franken-build system

Demo build systems are all alike; every real build system is convoluted in its own way - Tolstoy

At this stage, the usual technique is to split up your file into an index.html, and an index.js. The index.html imports index.js like so:

<script src="./index.js">

and that lets you write your HTML and JS separately.

To be honest, I should have just done that, which would shorted this section of the blog post, but I chose to inline the JS into the HTML file instead.

I knew that when I shipped the end product, I’d want to inline the JS into the HTML, for 2 reasons:

- Turns 2 network requests into one, which reduces the failure rate. For some reason, devs tend to assume that script loads never fail, which isn’t true. In my day job, I work on a web app which has a scale large enough that we have to be concerned about this.

- Improves efficiency of the gzip compressor, and thus smaller bundle sizes. From my investigations into the DEFLATE spec, I knew that gzip builds a dynamic huffman table for each block (about 16k symbols). Since I guessed that my entire HTML + JS file would fit in one block, this would decrease the overhead of compression since I’d only need to store one dynamic huffman table instead of two.

Of course, there are downsides to this approach, which you should be aware of:

- If your JS comes before your HTML, and your JS is big, it will block the page load. Usual solution to this is to put your JS after your HTML, but then:

- (cont) If your HTML comes before your JS, and your HTML is big, it will prevent the browser from compiling your JS code in parallel, which it can actually do.

- Increases complexity because now you have to inline the JS into the HTML somehow. Pretty much every bundler (Webpack, Snowpack, Vite) out there supports separate HTML and JS files as a default use case.

Without measuring, I’d say that if your HTML is more than 16kb, or if your Javascript files need to be split into multiple bundles, then it makes sense to split the HTML and JS files up for production.

Note that this has nothing to do with how you develop your applications, in which you should absolutely split your HTML and JS files apart.

At any rate, I made my life harder for your benefit. you’re welcome 😅

2.2 How to inline?

The process of inlining the JS wasn’t that glamorous, at the beginning I literally just copy and pasted everything from one file into the other manually. Eventually that got very error prone, so I did two things:

- Installed esbuild to produce a minified one liner file. Esbuild is a godsend to the JS dev tools world, and Evan Wallace should be praised a million times for this.

- Wrote a short Python script that ran esbuild and inlined this one liner at line number 54 of the file. Yes, it was hardcoded. No, I’m not (too) ashamed of this.

This terrible solution looked something like this:

1def replace_line(file_name, line_num, text, out_file_name):

2 lines = open(file_name, 'r').readlines()

3 lines[line_num-1] = text

4 out = open(out_file_name, 'w')

5 out.writelines(lines)

6 out.close()

7p = subprocess.run(["esbuild", "--minify", sys.argv[1]],

8 capture_output=True, shell=True)

9minified = p.stdout.decode("utf-8")

10replace_line(sys.argv[2], 54, minified, sys.argv[3])

After a while, I wanted to add CSS, so I inlined and minified that too with esbuild. Then, hardcoding the line numbers eventually came back to bite me as every time I updated the HTML file, I also had to update my python script.

To solve this problem, I added “template” tags to my HTML, which looked like this:

<style>

<% CSS %>

</style>

<script type="text/javascript">

<% JS %>

</script

My python script then looked for these (hardcoded) tags, and inlined the JS / CSS files there. Note the lack of indents on those tags, that’s because my first version of the script didn’t even bother trimming whitespace.

Eventually the Python script became the bottleneck in my build process. At 600ms it wasn’t too slow, but esbuild can parse, minify and print my entire JS code in under 8ms. My script does a lot less, so it should definitely run faster.

Instead of rewriting it in JS, another dynamic language, I decided to take a lesson from SumatraPDF’s build system. It’s entirely custom and written in Go.

Go is an excellent tool for writing build scripts, since the compiler is so fast that compiling + running a moderately sized build system is probably comparable to running an interpreted script. If you’re willing to precompile your build files, then the startup time becomes unbeatable.

So I wrote this little Go templater that did the same as my Python script (and also trims whitespace):

1// more above, this is the non boilerplate stuff

2scanner := bufio.NewScanner(templateFile)

3for scanner.Scan() {

4 l := strings.TrimSpace(scanner.Text())

5 if strings.HasPrefix(l, "<%") {

6 if replace, ok := replaceMap[l]; ok {

7 out.Write(l)

8 continue

9 } //fallthrough

10 } else if strings.HasPrefix(l, "<!--") {

11 // This is a HTML line comment

12 continue

13 }

14 out.WriteString(l)

15 out.WriteByte('\n')

16}

There are some asterisks with this templater (see Footnotes), but man does it run fast (~30ms). I got a 20x speedup, which is worth it if you ask me.

Lesson #2: Use the fastest build tools possible, because they prevent you from adding slower ones.

See the footnotes for my thoughts about the tradeoff between bundle size and build speed, in deciding not to add Terser as an extra minification step.

2.3 Bundle size tracking

One of the most useful internal tools I wrote was in commiting the bundle size to the repo, in a JSON file. It looks like this:

1{ "gzip": 10203, "parsed": 26314 }

It shows the gzipped size of the final bundled index.html, as well as the non-gzipped size. Parsed is an odd word, but it follows the terminology in webpack-bundle-analyzer.

This is extremely useful in helping you trace the history of your bundle size, and is basically a very simple version of a perf gate. It took me longer than I wanted to implement this, but once I did it I realized what a lifesaver it was.

So many times, I thought I’d found an optimization to reduce bundle size, but it only reduced the minified bundle size, not the gzipped bundle size. Previously, to figure this out, I would have to do a lot of manual work.

It’s surprisingly easy to set up. Go comes with a builtin compress/gzip, and using it as a simple as:

1var b bytes.Buffer

2zw := gzip.NewWriter(&b)

3zw.Write(outputtedHtmlFileAsBytes)

4gzippedSize := b.Len()

Since I had already written my own templater, it was pretty easy to add this in as a step after writing the index.html to disk.

2.4 Miscellaneous build decisions

2.4.1 Typescript or JS?

I switched to Typescript once I noticed that I couldn’t keep maintaining the code in a single file. I feel that’s about the right point to switch, since code within a single file is pretty easy to navigate without types, but between files your IDE can catch much more regressions than you can.

For the DOM stuff, I kept it in JS, since Typescript assumes the DOM operations are fallible when I know that the DOM elements will exist, and adding non-null assertions is really annoying. I moved all non-DOM logic into TS.

I don’t really have much more to say about TS, except that it is very, very good at catching regressions.

2.4.2 Formatting

I format my code with Prettier, with this prettierrc. I like longer print width since I dislike my code getting broken up too much.

1{

2 "printWidth": 120,

3 "arrowParens": "avoid",

4 "trailingComma": "all"

5}

2.4.3 Incremental rebuilds

I use Ninja for incremental rebuilds. There are a thousand and one incremental rebuild systems out there, so pick your favorite. I wouldn’t really recommend Ninja to everyone as it’s simple but not easy.

I was inspired to try out Ninja from Julia Evans, who wrote a neat blog post about using Ninja to build inkscape files. I also had some experience using it in college to build C++ projects.

Ninja’s main advantage for me is that it’s fast. Like, really really fast. It’s probably one of the few pieces of software that actually deserves to call itself lightning fast. A no-op build is 50ms, of which most of the time is spent in Windows’ CreateProcess call. Ninja itself finishes in 3.6ms.

To give you a taste, here’s what my rule to build my JS bundle looks like:

rule esbuild

command = node ./node_modules/esbuild/bin/esbuild $minifyOpts $in --outdir=$dist

build $dist/index.js: esbuild $src/index.js | $src/compile-guesses.ts $src/common.ts $src/filter-guesses.ts

As you can see, it’s quite tedious since you need to list out all the dependent files. The upside is that it’s not too hard to write a program to generate your Ninja files if you really need to, since the syntax is so simple. This means no time wasted in learning someone else’s opinion on what a build system should be.

3. Solving Wordle

Compared to the build process, solving wordle was a comparatively easier task. I honestly think that Software Engineering is more about the engineering than it is really about the algorithms.

First off, I had to come up with a way for users to input their guesses. Writing it into an input tag made the most sense, but how to input the “correct” / “wrong” status?

Since I primarily solve Wordle on my phone (so I can share it via Whatsapp / Signal), I looked at my phone keyboard and saw that , and . were prominently placed. So I decided to make it such that when you enter a letter, you can key in either a period or a comma afterwards, to mark it as correct or wrong, respectively.

Another approach would have been to allow users to enter their word into letter cards, then make them tap on each letter card to indicate the status, like Wordle does. That seemed promising, but I felt that that was too slow. I wanted to make something for power users (aka myself), and I knew that I would hate using that if I had to use it daily.

When I later released the app, I was worried people might get confused by the input scheme, but none of my friends seemed to have any issues with it.

I added a demo button that would input two carefully chosen guesses, to help people get used to the idea of using periods and commas to input the guess results, and that seemed to do the trick.

Lesson 3: People see, People do.

3.2 Sorting by frequency

(Update: Oct 2023 - I ran out of motivation for this blog post and stopped here. Still publishing this in case folks are interested in the rest)

3.3 Server Side Rendering (SSR)

One thing I never really appreciated until I got into web performance is how much of a difference there is between

- The browser parsing and rendering static html

- The browser using JS to create and add DOM nodes to your static html

Server side rendering is a way to get around this problem, where you pre-generate the DOM nodes that your JS has to create on app launch and bake them directly into the HTML.

Especially in page load scenarios, the difference is easily visible in a profiler. If you want to see for some graphs, this comment where I added SSR in as a PR on Github has screenshots of the profiler.

If you look at the screenshots in the comment, you’ll see a big long block Event: load in the non-SSR case: that’s the time taken for V8 to parse, execute, and create all the DOM nodes at load time. It’s about 100ms of time saved.

Usually, proper SSR is a pain to set up, which is why frameworks like Next / Nuxt / SolidSSR exist; these are for the React / Vue / Solid frameworks respectively. Since I’m not using a framework, I had to do SSR myself.

There is only one part of my website that is dynamically generated, namely the sorted list of words. When the page first loads, the user won’t have any guesses (unless they previously keyed in a guess and reloaded the page). In the common case, the list of words is always the same 100 words in the same order, so I was able to precompute the <li> elements for the top 100 words.

In the template, I added this field:

<ol id="suggestions">

<% SUGGESTIONS %>

</ol>

Which gets built and generated by these few lines of code in tools/make-suggestion-nodes.js:

1sortSuggestions(solutionWords);

2const html = solutionWords

3 .slice(0, NUM_SUGGESTIONS)

4 .map(makeSuggestionNodeHTML)

5 .join("");

6writeFileSync(suggestionsFilename, html);

A tiny optimization: per the HTML spec, <li> elements don’t have to have a </li> closing tag, as long as it is immediately followed by another list element, so I don’t put in closing tags in the generated SSR html.

Overall, this process added ~100ms to build time, ~400 bytes to gzipped size, but reduced page load times from 250ms down to 100ms, a major win.

3.4 Correctness

example:

Suppose the user got a result like this:

KROO,K,

this says that there is no K in the first position and last position. Furthermore, it says that there is exactly 1 K and exactly 1 O. function to filter

For instance, here’s some words that a naive algorithm might accept:

- CLOAK (wrong, since there one K, but it’s in the position marked wrong)

- KIOSK (wrong, since there are 2 Ks, and one O is on the position marked as not contained)

- KOALA (wrong, since there one K, but it’s in the position marked as not contained)

The filtering algorithm provided in kerrigan.dev accepts the last suggestion KOALA listed above, which is incorrect.

Footnotes

F1. HTML minification

Be careful at brazenly doing HTML minification by stripping newlines. If you look at the history of my templater, you’ll see a seemingly random if check that checks if a line begins with a open brace or close brace. That’s because this templater used to remove all newlines in the file. The problem comes about when Prettier sometimes breaks HTML tags into multiple lines. Here’s an example:

1<input id="abc"></input>

2<image

3 src="potato/a/b/c/d/e/f/potat.jpg"

4 alt="A potato"

5/>

In my templater, since I don’t do proper HTML lexing and parsing, this would have become:

<input id="abc"></input><imagesrc="potato/a/b/c/d/e/f/potat.jpg"alt="A potato"/>

Oops! <imagesrc is not a valid HTML tag.

In the time this blog post was written, I stopped stripping newlines because it cost me so much trouble. Here’s another example it would break on:

1<p>

210 apples are

3< than 20 apples because 10 < 20.

4</p>

This gets minified to:

<p>

10 apples are< than 20 apples because 10 < 20.</p>

Oops! There is a “are<” when it should have been “are\n<”, the line break is important for textareas.

In general, this is a classic example of why you can’t parse HTML with regexes. Your author fell into this trap and had to bail out.

Personally, I’m looking to switch to tdewolff’s minifier. But I haven’t had time to do it yet, and the savings seem minimal (about 40 or so bytes)

F2. Thoughts (aka rants) about Go

Every blog post involving Go has to have one, right? In my case, my big issue with Go is their inflexible build system.

Basically, I wanted to put my Go files in a nested directory and compile it there from my root directory. The command to do this is go build cmd/build_template, which builds the main.go file in that directory. First off, it took me an hour to figure that out, since the fact that go build can build arbitrary directories isn’t advertised that often. Then, Go insists that I create a go.mod file in my root directory, which I really didn’t want to do, since my project is NOT a Go project, but eventually I had to relent because there was literally no way to get around this limitation.

Regarding using Go for build tooling, I enjoyed it! Would do it again. It’s defintely more verbose than Python, but the speedup is worth it, and the Go standard library is just as good, if not better, than Python’s.

F3. Is it worth increasing build time to lower bundle size?

I have an open PR out for myself to consider adopting terser. Terser is an industry standard tool for minifying Javascript files, and it’s used by basically every big company except Google. Google has its own optimizer called the Closure compiler, which can compress JS better but at the cost of only accepting a subset of Javascript.

Using terser would decrease the bundle size by 140 bytes gzipped, which is quite significant at a 1.5% decrease in bundle size.

However, terser is only moderately fast, and it would add ~500ms to the incremental build times.

Should I add terser to this project as a default build step?